Hollywood, Streaming And The Decline Of The Hit Driven Business Model

Jan 18, 2023People have been predicting the end of Hollywood as we know it for a long time. Talking pictures were first dismissed as a novelty, then eventually embraced. Television proved destabilizing for the studio system that preceded it. And now, Chris Moore, a veteran of the hit-driven Hollywood business model of the 80’s and 90’s is bemoaning an underlying shift in the business, driven by the popularity in part of streaming services and behavioral changes unleashed by the pandemic.

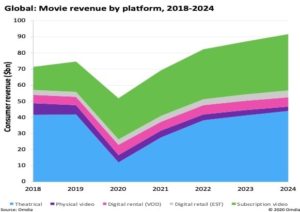

Image credit: https://celluloidjunkie.com/wire/cinemas-lose-32bn-global-box-office-revenue-in-2020-due-to-covid-19/

The concept of an arena

We have been trained to think of our economy as comprised of “industries” and within each industry competitive advantage meant that a firm did better than others that sell similar products and services. If that was ever true, and it’s not a bad place to start with a strategy analysis, in today’s environment the most significant competitor many players will strive to contend with may not even be in the same industry at all.

Instead, I’ve suggested that we can think of competitive arenas. Rather than the relatively closed spaces with clear rules of play that conventional strategizing suggest, I think of arenas more like open territory that different players are seeking to occupy – more like the Japanese game of “Go” than the more rule-based game of chess. In the case of competitive strategy, you are contesting with others to grab some key resource – usually money, but it could also be time or attention or something else that your model demands.

Netflix, for instance, has publicly said that in the past, they always considered their most important competitor to be sleep! Ironically, as the company has now observed huge new entry into the streaming business, shifting its economics, Netflix introduced new content aimed at helping viewers switch off!

Rather than the rigid model of releasing hot films first in theaters, content producers engaged in enormous amounts of experimentation. As things seem to be settling into more of a pattern, it remains to be seen whether they will re-establishing the ‘must see’ drivers that got moviegoers out of their houses and into theaters.

Jobs-to-be-done and customer needs

In addition to the arena idea, a second concept that is useful to look at what is going on in Hollywood is that of the job-to-be-done of the various ecosystem players. Clayton Christensen and Tony Ulwick are associated with the notion that we don’t actually want to buy products or pay for services at all. What we do is exchange our resources to get important jobs done in our lives. Further, the jobs themselves are often remarkably stable, even as the technologies used to achieve them change dramatically.

Consider the job of communicating across time and distance. In the past, we might have had smoke signals or marathon runners to get messages from one place to another. Then it might have been telegram, telegraph, landline phones, cell phones, smart phones, social media – you name it.

When caught in a business model transition, such as the one Moore is describing, the uncomfortable reality is that sometimes the business model that suits the organization best is one that customers are not particularly enamored by. This creates the opening for a competitor to come in, often using new technologies, and eliminate the frictions and displeasure created by the older model. And there are always going to be things customers don’t like about some aspect of an offering.

Consider mighty Gillette, which found itself on the wrong end not only of a pandemic, but of the new entry of hip players who developed personal relationships with their customers such as Dollar Shave Club and Harry’s. Customers thought the budget blades were good enough, and didn’t want to shell out for the more expensive (and awkward to buy) Gillette product.

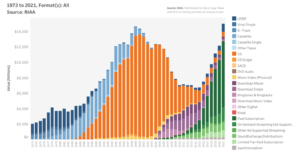

Or another example, which is very similar to the Hollywood example, when music distribution shifted from physical CD’s to streaming on services such as iTunes and Spotify. In pretty quick order, consumers figured out that they didn’t have to buy 12 songs they had no interest in to get the one that they wanted – they could just pick that one and pay a bargain-basement price for it at that. The resulting shift of how the industry makes money (as well as how artists are compensated) has been well-documented, as the graphic from the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) shows.

Source: RIAA

Changing jobs to be done for Hollywood

Which brings me to some observations that Moore is making about the current state of play in the movies. It isn’t so very unlike the period Hollywood went through when the monopoly power of the big studios was disrupted by both government insisting that they become more competitive and the advent of suburbanization and at-home television watching.

Streaming viewers behave differently than the classic visitors to a cinema. Rather than picking a movie (which could generate the buzz to create a hit), as Moore suggests, they pick a platform. The “job” is to remove the need to make choices, to have significant selection at the push of a button and to not have to make a big effort to bring interesting content directly to interested eyeballs. And for content producers, the mix of incentives to hold movies back for theatrical-only release has changed.

It doesn’t hurt that televisions themselves have become very sophisticated with technology that gets pretty close to what a cinema experience might be. Streaming has also closed off multiple revenue streams, such as international distribution and circulation of DVD’s which contributed to the “hit” status of a movie. The mental economics of streaming are interesting as well. Having already paid for a streaming service, paying more to see a movie in person can feel as though the user is being charged twice for an evenings’ entertainment.

It also isn’t only Hollywood movies that are experiencing a shift being forced on them by changing customer ‘job to be done’ preferences. Theater companies everywhere are reporting trouble getting customers off their couches to come back to in-person experiences.

Where will this all go?

Does the end of the “hit” system mean the end of the way the ecosystem used to be organized? Perhaps. And that isn’t all necessarily bad. Depending on hits to build a career is a little like being trapped in winner take all markets in other sectors. The system produces a few very well compensated and well known “winners” and everybody else is left out. The current developments may well lead to more participants in the creation and consumption of content as material is made available to people who were non-consumers before.

Streaming also fits well into the idea that our economy is moving toward more of a circular model with the consumption of experiences with low environmental impacts becoming more important. When many people can participate in the creative economy, perhaps that is one possible outcome.