We had the Jetsons in 1962, and autonomous driving is still out of reach

Nov 07, 2022Gradually, then suddenly. That’s the line that I borrowed from Ernest Hemingway to describe the progress of strategic inflection points. They brew along for a long time – sometimes decades – before finally breaking through.

The gradual, then sudden, pace of progress

Strategic inflection points – those events that punctuate a shift from one reality to another – feel as though they came out of nowhere. But as I’ve said in my book “Seeing Around Corners” the process of a fully fledged inflection point coming to life is often a very long one. I’ve been watching the autonomous, electrification space with respect to the investments being made by automotive companies, particularly Ford’s decision to pull out of its Argo AI investment, concluding evidently that the profitability of true level 4 autonomy is such a long way off that these investments no longer make sense.

This is a familiar story, particularly with technologies that are aimed at opening up an entirely new vector of functionality. Often, while the potential of the technology is huge, missing pieces mean that a later entry realizes the innovator’s ambitions.

The Apple Newton, for instance, failed, but was the first entrant into the field of “personal digital assistants” – Apple’s name for the category. Although it was widely mocked (famously in Doonesbury columns by Gerry Trudeau) for its inability to recognize handwriting, the technology showed the world that computers could leave our desktops and move into our pockets. The subsequent success of the PalmPilot, the Sidekick, and of course the modern smart phone, all derive from discoveries made pursuing the vision behind the Newton.

We’re seeing the same thing across many fields. Take the area of consumer robotic technology. Well-funded companies with names like Anki, Jibo and Kuri struggle with social engagement, maintaining usefulness and meeting consumer expectations. And yet, as the Wall Street Journal’s Christopher Mims describes, early stepping stone markets in industrial robotics and B2C markets illustrate that these are problems that can be solved, piece by piece. Widespread adoption of robots in response to an aging workforce, increasing costs of labor and greater control and predictability for employers is a matter of whether, not when, would be my main conclusion.

So let’s go back to our flying autonomous car, science fiction future and see how we got here.

The autonomous vehicle in history

Humans are ingenious – able to imagine the existence of things that don’t yet exist. So, too, with autonomous cars. In fact, Leonardo Da Vinci is credited with designing the very first autonomous “vehicle” – a cart that could move by itself using wind-up springs, like those you might find in a child’s toy. While it never got off the drawing board in his lifetime, or for many lifetimes after, his 1478 speculation was finally brought to real life in 2004.

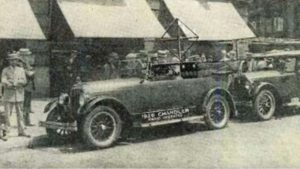

Somewhat closer to modern applications of driverless cars was the 1925 journey of a car called the American Wonder. Invented by former U. S. Army electrical engineer, Francis P. Houdina, it was a Chandler sedan that he rigged with a transmitting antenna which controlled small motors, which in turn controlled the steering wheel and pedals. It took a triumphant journey along Broadway and Fifth Avenue in New York, narrowly avoiding one crash, only to drive headfirst into another vehicle full of photographers gathered to cover the event!

Photo credit: https://www.tomorrowsworldtoday.com/2021/08/09/history-of-autonomous-cars/

In 1935, author David H. Keller, in a short story called “The Living Machine” extolled the virtues of a car without human beings behind the wheel. Irritated at the thought of any stupid human who could assemble the cash to buy a car and start driving, he envisioned a much safer world of driverless transportation. “Old people began to cross the continent in their own cars. Young people found the driverless car admirable for petting. The blind for the first time were safe. Parents found they could more safely send their children to school in the new car than in the old cars with a chauffeur.”

That same year, 1935, General Motors released a commercial featuring self-driving cars to emphasize how much safer they would be than the human-powered version. Back then, so many people died in traffic accidents that lawmakers and opinion leaders debated whether the automobile was inherently evil. It took a long time for safety protections we take for granted to be implemented. As the Atlantic reports, “Eventually, traffic laws and other safety features—stop lights, brightly painted lanes, speed limits—were standardized. And car-safety technology improved, too. Vehicles got shatterproof windshields, turn signals, parking brakes, and eventually seat belts and airbags. In 1970, about 60,000 people died each year on American roads. By 2013, the number of annual traffic fatalities had been cut almost in half.”

Chasing the driverless dream

General Motors funded a theatrical vision of a driverless and car-centric future at the 1939 World’s Fair in an exhibit called “Futurama” that proved remarkably predictive of the growth of car-dependent suburbs after World War II. This development, while promising convenience, led to sprawl, long commutes, cities starved of resources for investment in mass transit infrastructure and inequities in access to social resources that are today widely recognized as problematic.

In the early 60’s, efforts to come up with a vehicle that might be controlled remotely on the Moon led to the invention of the Stanford Cart, a bicycle-wheeled contraption with a camera that could (if clumsily) be operated remotely. That project was abandoned when President John F. Kennedy announced that we’d be sending actual people to the moon, presumably meaning that they would do the driving if there was driving to be done.

By the 1990’s, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University were at the forefront of robotics, and driverless mobility. By 1995, their NavLab 5 driverless car made its famous “no hands across America” tour, traveling 2,797 miles from Pittsburgh to San Diego.

By the 2000’s, pursuit of the autonomous car dream was becoming hot and heavy. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) announced a Grand Challenge, with a million-dollar prize for a team that could complete the journey from Barstow, CA, to Primm, NV, in 2004. The prize money went unclaimed – nobody finished. The following year, a team from Stanford won a $2 million prize and five teams in total completed the route.

This yielded unparalleled optimism. As the DARPA report reads, “These challenges helped to create a mindset and research community that a decade later would render fleets of autonomous cars and other ground vehicles a near certainty for the first quarter of the 21st century.”

A self-driving Prius made its first drive on public roads in 2008, attracting attention from the public at large and serious fear-of-missing-out by just about every organization that touches the mobility business.

But wait, do we really understand the implications of autonomous vehicles?

It’s quite common when thinking about the future for people to project a change in one part of the system while holding the rest of it constant. Even the Jetsons!

The show had flying cars and robot servants, but social roles and workplace norms remained firmly grounded in 1962 when it premiered.

Source: https://ew.com/tv/the-jetsons-casting/

As we think about the driverless car system, it quickly becomes obvious that there are a lot of unintended consequences such a technology might unleash. Cory Doctorow points to one, which is that for every human being on the planet to conceivably get around in single-person transport requires an unrealistic amount of ground to be dedicated to that purpose. Moreover, as Jacob Silverman of The New Republic argues, “We need people biking, walking, taking buses and trains and subways, or otherwise riding in something besides a free-ranging, 3,000-pound metal exoskeleton with an error-prone operator, digital or human.”

To look more holistically at what the future holds, I’m a huge fan of Amy Webb’s Future Today Institute. There are a ton of tools and resources at their web site, and you can also listen in on our Friday Fireside Chat in which she lays out some of the most common pitfalls people encounter when they think about the future.

Meanwhile, at Valize

We’ve developed a deeply researched team effectiveness diagnostic that allows you to get to the bottom of why so many teams don’t work very well and make interventions to correct them. We’re offering the first ten teams to sign up before the end of the year the opportunity to run the diagnostic and have a customized one-on-one debrief with myself and the Valize team. It’s $125 per team member plus $2,900 for the customized debrief plus results report.

It can be magical! Complete the contact form on the Valize website to learn more.

*Originally published on Thought Sparks