What everybody ought to know about planning under uncertainty

Apr 18, 2022

The article “Discovery Driven Planning” was published in 1995. The book-length treatment came out in 2009. And yet, we’re only now catching up to what entrepreneurs and corporate innovators have long understood – when you are dealing with uncertainty, you need a plan to learn.

If it were ever possible for business leaders to opt out of having to deal with uncertainty, it definitely isn’t the case today. COVID, snarled supply chains, an end to globalization as we knew it, technology advancing in unexpected ways – you name it, there is no predicting what’s likely to happen next week, let alone over the length of your strategic planning cycle. Don’t despair – using the lens of being discovery driven, you can carve out a path that may not be predictable, but is at least lower in risk.

Creating breakthrough growth in a systematic way

Discovery driven growth involves pursuing your objectives under uncertainty in a way that is both pragmatic and low risk. The essential discipline is to specify a future that is attractive, then work backward into what would have to be true today, the next day, the next week, the next month, and so on. It’s a very different approach than conventional planning on several dimensions. It also requires different behaviors from leaders.

Definition of success

In conventional management, leaders are assumed to be able to anticipate contingencies and plan with a great deal of knowledge. Success is therefore often defined as making your numbers and hitting projections. With a discovery driven mindset, in contrast, success consists of learning as fast as you can, as cheaply as you can, to make progress toward goals.

Success, and its counterpart, failure, actually work together when you are operating in a discovery driven way. Rather than expect leaders to have the answers, instead what you are doing is articulating what your best hypothesis is, given what you know, then devising a way to test the hypothesis. If it isn’t supported, that’s just one dead end you don’t have to pursue. Better to find it out fast and before anyone else does than wait and have to undergo an expensive “pivot” later on.

Management timeframe

Despite all the moaning about short-termism in management, it is true that in a conventionally run organization managers spend the vast amount of their time on day to day and operational issues. That’s what got most of them promoted, after all! Today’s problems always look as though they will be devastating without managerial attention and they yank people away from a future oriented focus. The urgent often drives out the important.

In a discovery driven organization, in contrast, senior leaders spend a disproportionate amount of their time on the future. Jeff Bezos of Amazon famously talks about how he and his entire management team “live” two to three years into the future. The operational items are either turned into what Amazon calls “mechanisms” or are delegated to leaders with more focused areas of impact.

Timing

In conventional planning, the annual rhythm of a budget cycle typically dictates a lot of the timing of corporate decision-making. Strategy is often a footnote, as managers argue backwards and forwards about what numbers should be committed to and when certain objectives are going to be delivered. The whole process is hugely time consuming and once its done, nobody wants to go back and revise it. This is a flaw that tools from our good friends over at the Beyond Budgeting Institute addresses.

With discovery driven growth instead, timing and the related discipline of timing is geared toward the accomplishment of key checkpoints. A checkpoint is a moment that is going to teach you something – a test of a hypothesis, for instance. Will at least 10% of visitors to your web site click through? Put up a web site and check it out!

A company investing in breakthrough innovations is also patient with respect to time. Indeed, former SRI International CEO Curt Carlson talks about some projects requiring five years or more to gestate to eventual market entry.

Changes in direction

Although the lean startup movement has made people more tolerant of pivots than perhaps they were before, in many organizations there is still a sneaking sense that if you had to make a change in direction or revise your plan that you got it wrong. Drucker’s well regarded “management by objectives” approach suggests that both leaders and those working with them can articulate clearly what goals are to be met and with what means.

In a discovery driven situation, however, with high levels of uncertainty, one can articulate what success would look like, but not necessarily how to get there. In such cases, making a revision to your plans isn’t a bad thing at all. It reflects learning. Indeed, sticking to the same approach when something isn’t working isn’t perseverance, its obstinacy!

Project redirection and disengagement

Shrinking or stopping a project is often considered a really bad thing. After all, it was probably approved with hundreds of pages of PowerPoint notes and tons of annotated spreadsheets (with the duly placed hockey stick of growth at the 3 to 5 year mark). It may well have been fully staffed with costly people and technological talent. It may have even been promised to investors as the Next Big Growth vector for the company, as was the case with Motorola’s spectacular flop, the Iridium project. All of these forces create enormous pressure on project leaders to continue, no matter what. This even has a scientific name – the escalation of commitment to a failing course of action.

With a discovery driven mindset, instead, you want to be thinking of projects as options. An option is a small investment you make today to figure out whether a larger investment is merited. Because it’s small, you can keep the approval process light. Because it’s small, stopping it doesn’t’ cost you too much. What you are after is a mindset that says, “I’m willing to risk $200,000 to figure out whether there is a $20 million opportunity there.” Then you release your funds and increase your risk only as new information suggests that makes sense. Redirecting a small project early is easy. Redirecting a big project late is hard.

Approach to Funding

Because most budgeting programs assume considerable certainty, new ventures are often set up as though they were established businesses. This often results in their having all their funding allocated at once (which we’ve already established is a bad idea). Worse, it also often results in funding being unpredictable. Let the parent company have a bad year, and the easiest things to cut are those new little ventures that haven’t demonstrated market acceptance yet. This means that innovations, even if they are making progress, get whipsawed. It’s hard to make progress with an episodic innovation program.

In a discovery driven world, a funding approach over a multi-year timeframe takes over from a budget approach with a fixed timeframe. Funds are only released as a venture crosses critical milestones, similarly to the way in which venture capital firms approach the release of funds. Like venture capitalists, there is no guarantee that having funded one round that the venture will continue to the next. Funds, further, are ideally allocated from a central corporate budget, not from the budget ‘owned’ by a business unit leader.

Assumptions

In uncertain conditions, the ratio of assumptions one needs to make to knowledge that one has is high. Everybody knows this. What everybody doesn’t do, or do with enough discipline, is to document those assumptions and develop a clear path to testing them. In fact, in many organizations even to state that a decision is being based on assumptions is regarded askance.

Managing assumptions is really hard. And decisions made by human beings suffer from literally hundreds of biases, distortions and habits of mind that lead us to mis-manage them.

For instance, we turn them into facts in our minds and then the confirmation bias leads us to seek out information that supports those facts, even in the face of strong evidence that they aren’t true. This has been listed as a factor in vaccine hesitancy, despite strong scientific evidence that vaccines are effective against COVID-19.

Or we forget the assumptions that were on our minds at the time a decision was made, meaning that we’ve lost the ability to learn when later events are inconsistent with those assumptions. Hint: write them down and revisit them periodically – it’s a great discipline.

Or we don’t realize the cascading effect of just a few assumptions on the entire system. This was at the heart of the disastrous Long Term Capital debacle in which a giant hedge fund nearly took down the global economy because its traders failed to account for an unpredictable amount of volatility in foreign exchange transactions. The firm was bailed out, unfortunately presaging a similar crash when traders failed to properly price mortgage-backed securities some ten years later.

Downside risk

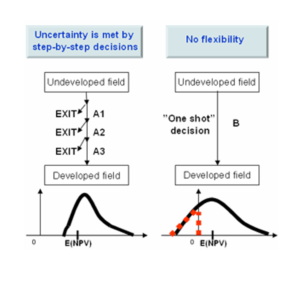

An options oriented rather than a full-on venture launch allows you to be smart about managing risk. At each decision point as your venture unfolds, you can ask the question “does the upside still justify the continued investment?” If the answer is no, then you can stop. This offers you the benefit of knowing at each step along the way what your exposure to the next step is.

You can think of it this way – if the potential outcome of your innovation was distributed along some kind of normal curve, half of the time you would be losing money and half of the time you’d be gaining some. With an options style approach, you can essentially choose to avoid the downside by not making further investments.

This illustration of the investment approach from the oil and gas industry shows what that looks like:

Try it – it actually works and you can learn how.

Although it isn’t part of every leaders’ toolkit – yet – the discovery driven approach is pretty straightforward. Its benefits are tremendous – faster learning, lower risk, and a way to get everybody on the same page with what we all believe to be true.

I’m offering a short on-line course that teaches the technique so that you or members of your team can learn it. You can learn all about it at this link.

We’re also creating a cohort of learners for our longer 6-week module program that is all about how you can create competition-beating customer insights. I’ll be popping in regularly for professor office hours and to help if people get stuck. Sign up for yourself or bring a team! Going through it might be a great opportunity to head into the summer with a brand-new set of skills.